|

|

|

THE HIDDEN FACTOR IN REALLY BEAUTIFUL SINGING:

TRACHEAL RESONANCE

by Clayne W. Robison

Most attractive singers have a bright, speech-like quality in their voices. We

don't have any trouble understanding the words they are singing. Their sound

reaches out and grabs us. Teachers draw that out of singers by talking about

projection, or singing forward, etc. But the voices that really melt us also

have a quality of depth to them. There is something that makes us feel like

the sound is coming from the bottom of their souls. The brightness in their

voices speaks out to us, while the depth is drawing us in. When both things

happen at the same time we know we are hearing really beautiful singing.

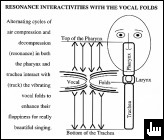

In April 1992, Ingo Titze, Director of the National Center for Voice and

Speech in Denver, and one of the world's foremost vocal physicists tried to

create a computerized model of Luciano Pavarotti's voice. Drawing assumptions

from the new interactivity or "chaos" paradigm in physics, he was able to get

his computer to sound like a fairly good singer by plugging in formulae for

the more easily measured brightness kinds of things coming from the "top" part

of the voice - resonances from the vocal folds through the pharynx clear up to

the speechy articulations at the lips and tongue. But he didn't start

calling the sound "Pavarobotti" until he also plugged in mathematical formulae

for the depth factors - resonances hidden in the trachea behind the chest. Up

to that moment even the most sophisticated scientific equipment had not been

able to identify or measure these deeper elements. Only computer modeling

told the truth about these keys to really beautiful singing.

calling the sound "Pavarobotti" until he also plugged in mathematical formulae

for the depth factors - resonances hidden in the trachea behind the chest. Up

to that moment even the most sophisticated scientific equipment had not been

able to identify or measure these deeper elements. Only computer modeling

told the truth about these keys to really beautiful singing.

The beautiful singer recognizes these resonances as a fragile buzzing

sensation behind the chest. The Italians call it appoggio, or "breath

leaning against the chest." It feels like the drone of a tiny bagpipe playing

at a single continuous pitch underneath all of the other pitches being sung.

It is very subtle, which probably explains why it has eluded both scientific

probing and open pedagogical discussion. Teachers have called the rare

students who had it by nature"talented" and have done their best with the rest

of the students. Titze's tracheally resonant Pavarobotti has opened

discussion that will change the way we teach singing. From now on, if it

doesn't come by talent, we'll put it there with physics.

The moment I discovered this phenomenon behind my own sternum was the most

illuminating moment in my singing life. I give credit to my former BYU voice

teaching colleague Ray Arbizu, who possessed a stunning lyric tenor voice. As

we were returning from Salt Lake City to Provo one evening from a rehearsal

with Utah Opera, Ray said to me, pointing to his chest, "Clayne, you got it

right tonight. That was really beautiful singing." That finger pointing

downward in front of his chest had been a familiar signal from Ray. We had

all seen him point there often in student recitals and juries and had tended

to make fun of it as his strange trademark - just another of those unique

eccentricities to which singing teachers are prone. But this time his

compliment of my evening's singing caught my ear, and we had some travel time

to explore it. I tried to find it again, singing while driving. But he kept

shaking his head and tapping his chest. Finally, I sat up straight, took an

easy low breath and let go with a sound that satisfied him. He had me repeat

it several times until I could feel the subtle little drone in my chest. It

felt right - the way I had been singing an hour earlier at the opera house in

Salt Lake City.

Several ideas can help your body find and maintain this subtlety in your own

singing. A very low, easy in-breath will help you preserve the sensation of

inhalation even during singing. This continuing inhalation feeling elongates

the center of the lung sack and tugs down on the trachea imbedded in it,

putting it in position to be a good resonating chamber. From the instant you

start to sing, however, you must also use the flowing breath to inflate or

"pop open" the chest so that the tracheal buzz can be generated.

Several ideas can help your body find and maintain this subtlety in your own

singing. A very low, easy in-breath will help you preserve the sensation of

inhalation even during singing. This continuing inhalation feeling elongates

the center of the lung sack and tugs down on the trachea imbedded in it,

putting it in position to be a good resonating chamber. From the instant you

start to sing, however, you must also use the flowing breath to inflate or

"pop open" the chest so that the tracheal buzz can be generated.

When you are singing really beautifully, this fragile tracheal buzz feels,

in a way, like it has been "moaned" into being . That moaning sensation,

preserved as an uninterrupted constant throughout the entire phrase being

sung, is a sign that full, balanced interactive physics is at work in your

voice.

Maintaining uninterrupted interactivity

The idea that the voice can be completely interactive has profound

implications. Among other things it implies the following, all of which Dr.

Titze had to account for as he synthesized the Pavarobotti sound:

- Vocal onset is critical. If the singer does not at the

instant of vocal onset interactivate all of the major oscillating factors

needed for beauty in the coming phrase, he will find it nearly impossible to

recapture those missing beauty factors later in the phrase.

- Initial interaction of the extremities is critical. If at

the instant of onset the breath-creating activity (way down in the floor the

abdomen) can interact freely with the articulatory activity (clear up at the

lips and tongue), it is likely that the intermediary systems (the vocal folds

and the resonance chambers both above and below them) will be drawn into the

optimum interactive web for the succeeding vowel. In other words, get the ends

working together and the middle is more likely to fall into place.

- Legato line is critical. Once all of the factors required

for vocal beauty have been interactively engaged at onset, they should continue

to be interactively carried from note to note right through the pitch changes

as well as through the speech-like articulations. To allow them even slight

disengagement during the movement from note to note or vowel to vowel, or even

during the consonant articulations, will again require a total realignment of

the interactive network for the next note, vowel or consonant. In fact clear,

fully energized articulation can be used to create a balanced back pressure

against the lips and tongue that maintains the openness of the resonance

cavities for the entire stream of vowels in the phrase. The voice that tries

to regenerate its interactivity on each and every note is not a beautiful

voice. I call it a "link sausage" voice. It is impossible to decide whether

the "moaning" legato line of the beautiful voice is more the result of a

totally consistent stream of vowels or a consistently energized stream of

consonants or (most probably) both.

to be interactively carried from note to note right through the pitch changes

as well as through the speech-like articulations. To allow them even slight

disengagement during the movement from note to note or vowel to vowel, or even

during the consonant articulations, will again require a total realignment of

the interactive network for the next note, vowel or consonant. In fact clear,

fully energized articulation can be used to create a balanced back pressure

against the lips and tongue that maintains the openness of the resonance

cavities for the entire stream of vowels in the phrase. The voice that tries

to regenerate its interactivity on each and every note is not a beautiful

voice. I call it a "link sausage" voice. It is impossible to decide whether

the "moaning" legato line of the beautiful voice is more the result of a

totally consistent stream of vowels or a consistently energized stream of

consonants or (most probably) both.

Your really beautiful voice maintains a seamless interactivity that is

constantly both bright and deep - both "up front" and inscrutable, both ice and

fire.

|

|